A patient under anesthesia for open chest surgery.

A very common question is: “I’ve heard that XYZ breed doesn’t take the amount of anesthesia you would think for their size.”

I’ve heard this question about countless breeds. Newfies. Greyhounds. Mastiffs. Keeshonds. Dalmalabracockadoodles. And many more.

For the most part, this is an urban legend, and nobody knows where it started.

Nothing we do is cookie-cutter in our practice.

Everything we do is tailored to each patient.

A shepherd under anesthesia to repair a broken bone

Let’s go over the 3 main parts of anesthesia.

1. Induction

Induction is the short time it takes for a patient to go from sleepy to anesthetized.

Before induction, every patient has received a tranquilizer and/or doggy or kitty morphine, specifically so they need less anesthesia.

Some “at risk” patients might receive other drugs. Patients with a mast cell tumor receive Pepcid and Benadryl. Patients with a flat face receive Pepcid and 1 or usually 2 anti-vomiting drugs.

And so on and so forth. “Every patient is different.”

We then place an IV catheter, through which a drug is given “to effect.”

That drug, most often, is propofol.

Giving it “to effect” means that we have a theoretical, calculated amount based on the patient’s weight, but we give it very slowly, until the patient is relaxed enough to place a plastic tube down their windpipe.

Most of the time, we don’t even need to give the full amount.

Now, in some at-risk patients, we don’t use propofol but a drug called alfaxalone.

We tend to use it in at-risk patients: C-sections, sight hounds, cardiac patients, seizure patients, pediatrics under 3 months of age, geriatrics, and debilitated patients.

2. Anesthesia

That’s when anesthesia per se begins.

The plastic tube delivers mostly oxygen, with a small percentage of an anesthesia gas called isoflurane.

The maximum an anesthesia machine can deliver is 5% gas.

Because we give so many pain medications, it’s not uncommon that patients are kept at a MAXIMUM of 1% gas, and therefore 99% oxygen.

Even better: we routinely perform invasive surgeries on 0.75% gas.

A good nurse will take it as a challenge: how to keep her patient pain-free, with the least amount of gas possible.

The size and weight of the patient is irrelevant.

Of course, a large patient will receive more oxygen, but not necessarily more gas, since it’s given as a percentage.

So a Chihuahua may need 2% gas, and a Mastiff may need 1%. It all depends…

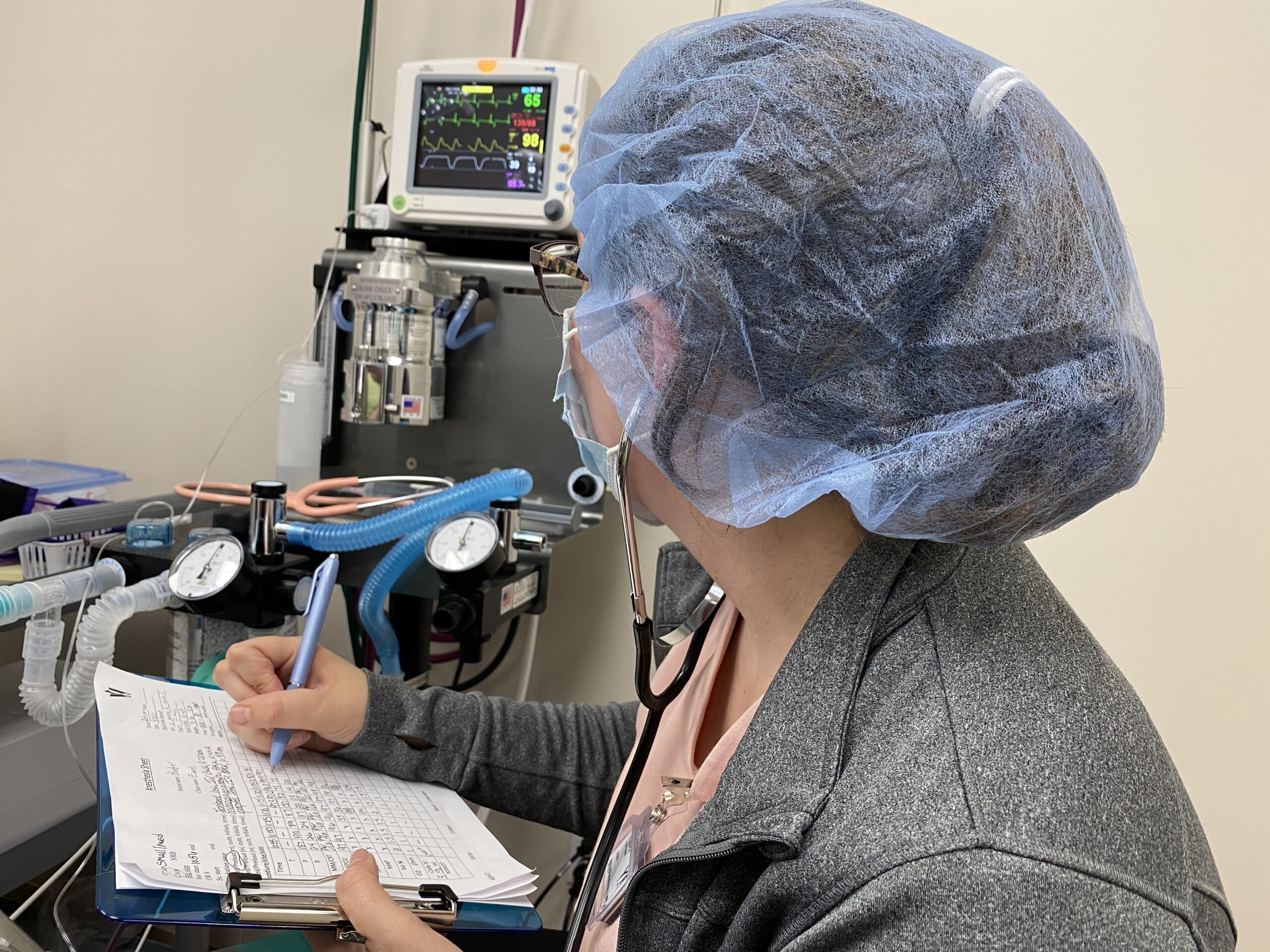

Every patient under anesthesia has a dedicated anesthesia nurse

3. Recovery

Although many pet owners are scared of anesthesia, the higher risk is AFTER anesthesia, not during.

This is the reason why we continue to monitor patients closely as they wake up from anesthesia.

We’re even more paranoid with dogs with a flat face (brachycephalic breeds) such as Bulldogs, because they have an even higher risk of getting in trouble.

In addition, whatever the size, species, and breed of the pet, each patient has their own dedicated anesthesia nurse, whose mission is to monitor them and keep them safe during the entire anesthesia process.

All of the above thoughts apply to the vast majority of patients.

A bulldog under anesthesia for “upper airway” surgery, including a nose job.

And occasionally, a particular dog may have a legitimate higher sensitivity to anesthesia drugs.

. Sighthounds (e.g. greyhounds) do have genetic factors that make them metabolize drugs more slowly.

. Some herding dogs (e.g. collies, border collies, Australian shepherds, Shelties) may have a true sensitivity. It is explained by a genetic mutation in a specific gene. It is now called the ABCB1 gene, but used to be called the MDR1 gene.

Up to 75% of collies in the United States might be affected!

The consequence is that some drugs accumulate within the brain, and can affect recovery from anesthesia.

As you can see, the fact that a particular breed needs less anesthesia doesn’t really mean anything.

It all depends… and it’s a bit more complicated than that.

So what do we do?

. We discuss the anesthesia and pain management protocol for each patient as a team (surgeons and nurses) so they are adapted to the patient and their particular surgery.

. For example, we use a different protocol for pets with kidney, liver and heart disease.

. We use a special protocol for dogs (and cats) with a flat face (English Bulldogs, French Bulldogs, Boxers, etc.).

. We use a different protocol for diabetics and pediatrics.

. We assess the patient’s individual anesthesia risk (called the “ASA” risk).

. We always give the minimum amount of propofol required for an individual patient during induction.

. We always give drugs based on what an individual patient may need.

. We may need to avoid using some drugs, or reduce the amount of drugs in some truly at-risk patients.

. And we always give the minimum amount of anesthesia gas required for an individual patient during anesthesia.

Ultimately, our goal is to design the safest anesthesia plan for each individual patient.

As we always say, “every patient is different.”

If you would like to learn how we can help your pet with safe surgery and anesthesia, please contact us through www.LRVSS.com

Never miss a blog by subscribing here: www.LRVSS.com/blog

Phil Zeltzman, DVM, DACVS, CVJ, Fear Free Certified