Can you imagine what it must feel like to live with the conviction that your pet has cancer for 9 months?

“Stress, anxiety and panic.”

But let’s go back in time a bit.

Nine months ago, Mollie, a sweet and loving 10 years Lab, “had an episode where she was lying on her side, on the floor, unable to get up, with a rigid abdomen,” her owner recalls.

They brought her to the ER in the middle of the night.

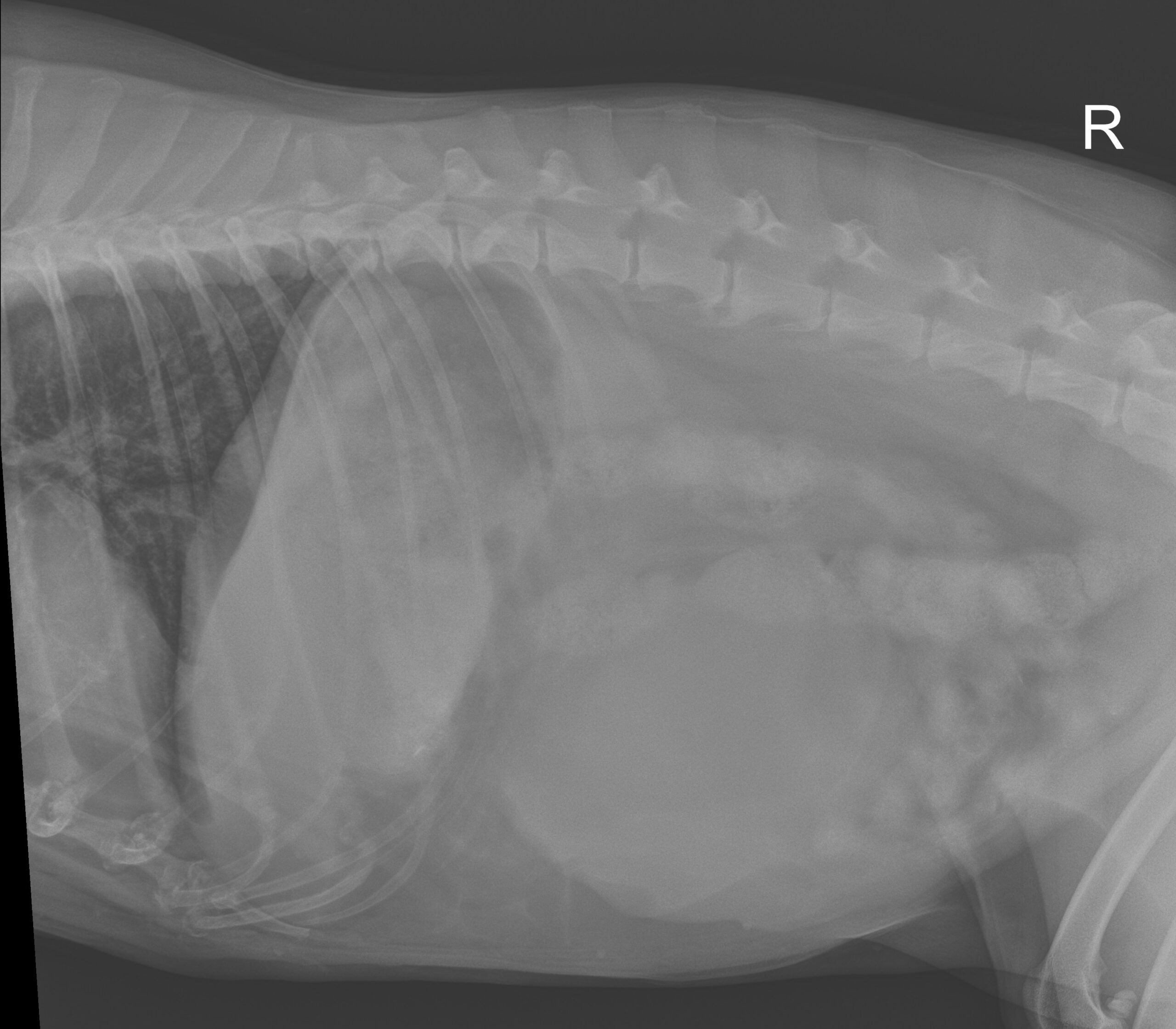

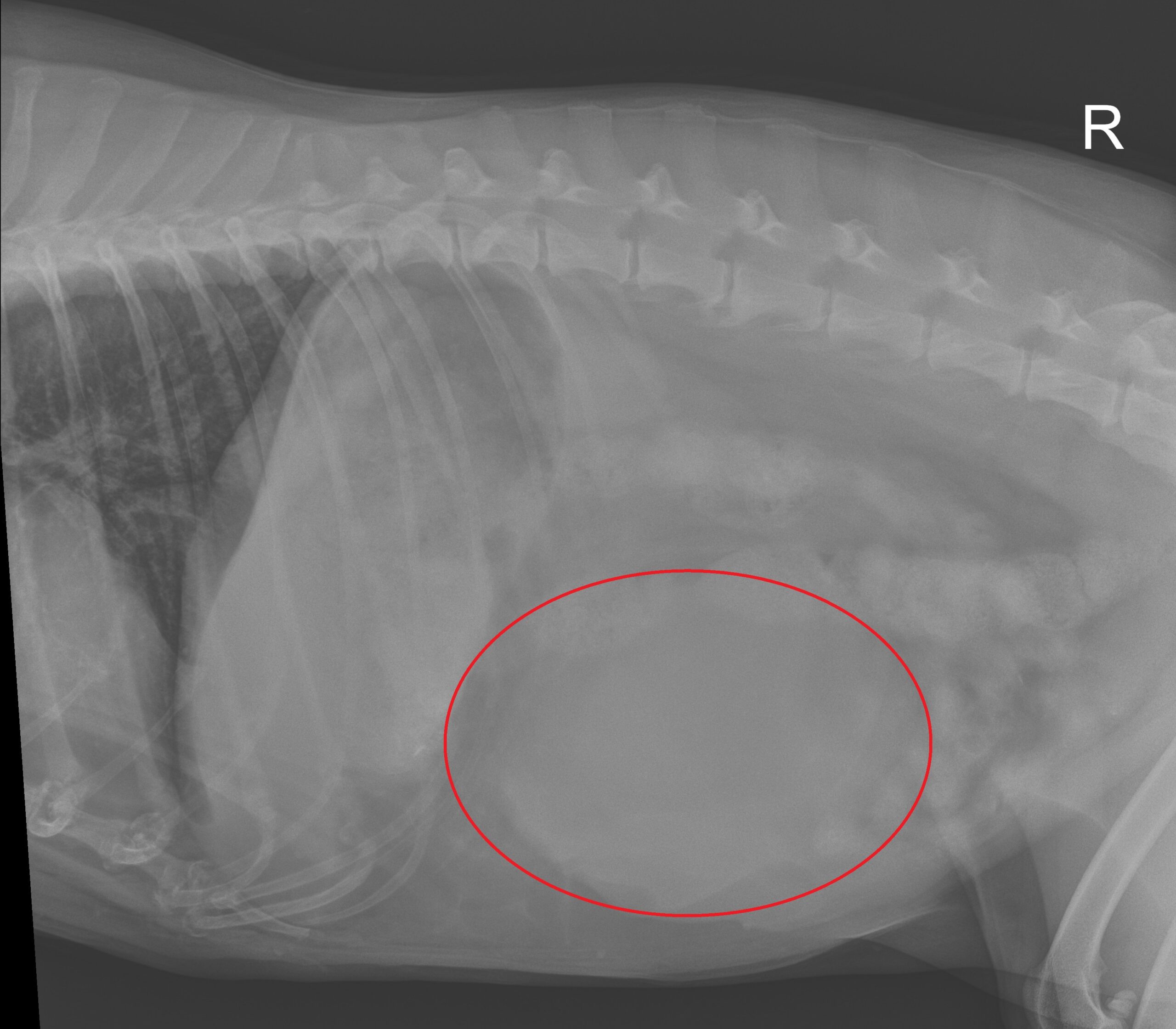

X-rays revealed “a large tumor” and internal bleeding.

Can you see the mass?

The ER vet proclaimed that this was most likely spleen cancer (specifically hemangio-sarcoma).

The mass is inside the red line

And he went on to predict that “she would likely die from this bleeding episode within hours to days.”

Then he advised that “surgery was dangerous because the tumor was highly vascularized and she would likely die on the table.”

And he recommended euthanasia.

Fortunately, Mollie’s owner didn’t follow this recommendation.

The only “treatment” offered was Chinese herbs (Yunnan baiyao) to help with internal bleeding.

They “took her home and waited for the end and hoped she wouldn’t suffer.”

But guess what?

Mollie didn’t die at all!

She made a full recovery.

(Otherwise, there wouldn’t be a story to tell, would there?)

Encouraged, Mollie’s owner called her family vet.

The new recommendation was to “watch and wait and avoid a dangerous surgery.”

Things finally changed during Mollie’s annual exam.

Her owner recalls: “We met with another vet and had a long conversation about our options. We agreed to get an ultrasound, chest X-ray, and blood work to rule out metastasis (spreading of the cancer). Everything was negative! That opened up a lot of other possible diagnoses other than hemangio-sarcoma (cancer) of the spleen.”

Three surgeons were recommended.

The owner recalls: “We only spoke to ancillary staff at the two recommended by our vet. We spoke directly to you about Mollie. You seemed to be the most positive and interested party in Mollie’s case.”

I told Mollie’s owner what I tell all of my clients who use words like cyst (usually meaning good or benign) or tumor (meaning good or bad) or cancer (obviously meaning bad) that we just don’t know what we’re dealing with yet.

So we were dealing with a mass (a completely objective word) until proven otherwise.

Then I said that I don’t have microscopic vision, and the only people I trust to give us the real diagnosis are the pathologists at the lab, who will look at samples under the microscope.

Until then, anything else is an assumption, or a (hopefully) educated guess at best.

On surgery day, Mollie’s owner “felt nervous but committed to try to help my happy, otherwise healthy dog. We felt strongly that she needed the surgery and would do well.”

“We just felt that based on what we were told, the treatment was dangerous and serious.”

The owner tried to express the stress they’d endured for 9 months before surgery: “This situation has been a constant source of stress and anxiety. Every day you check her. If she didn’t come right away when you called her, there was a sense of panic. We spend a lot of time with our pets. We don’t travel frequently and we limit how long they are alone in the house. This has been tough. We were devastated that our very young-acting 9 year old dog had this terrible diagnosis. (My husband) never really had faith in it though. He always felt that they wrote Mollie off too quickly.”

Over the 9 months since the ER visit, and despite one lesser bleeding episode after that, Mollie “never appeared unhealthy or uncomfortable. Her abdomen continued to grow but she never appeared unwell except for the two episodes.”

She continues: “The day before surgery, there was a little bit of panic. We had to remind ourselves that if Mollie did not survive the surgery, our decision was in her best interest to save her. If we did nothing, she surely would have succumbed to whatever was growing inside of her.”

On D-Day, Mollie was placed under anesthesia.

Once she was set up on the surgery table, you could see (and feel) a big bump in her belly, as shown in the picture below.

This is the only tame picture. Following pictures will be very graphic.

CONTINUE READING AT YOUR OWN RISK.

Some pictures are not for the faint of heart.

You can see the bump under the skin, between the blue arrows

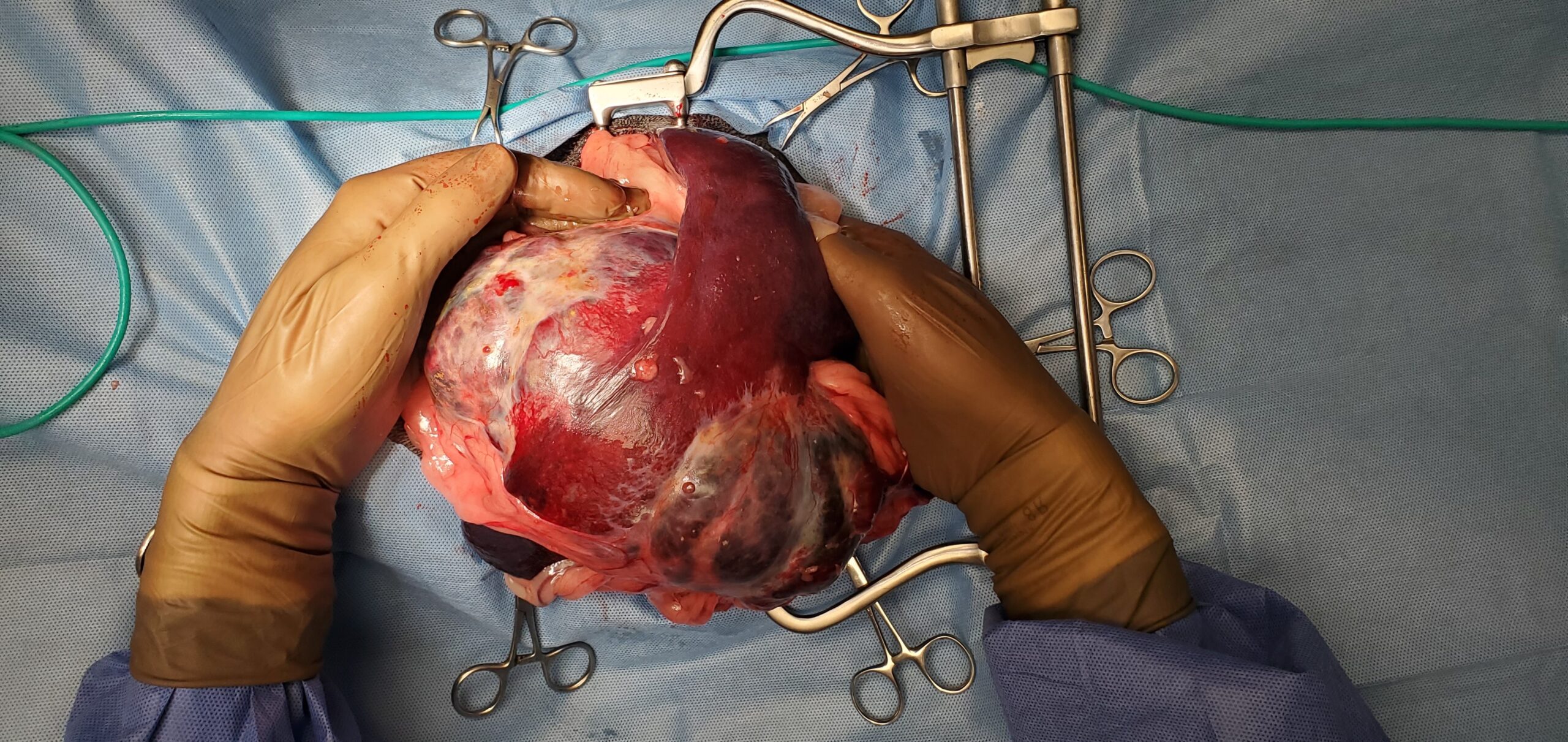

Once the belly was opened, a large mass appeared on the spleen. It was so large, that we had to open the belly incision more to safely remove the mass and the spleen without rupturing it and causing bleeding.

You can get an idea of the size of the mass compared to my hands

Surgery was straightforward.

Once the spleen was removed, we looked at every single organ in the belly. They all looked good, including the liver, where cancerous masses commonly spread.

Below is the picture of the actual, attached to the spleen, mass after surgery. The whole thing weighed a whopping 5 pounds (Mollie the Lab weighed 67 pounds before surgery).

After her belly was stitched up, Mollie recovered smoothly in ICU.

After one night on IV fluids, antibiotics and pain medications, she went home the next day.

When she saw her walking out of LRVSS, her owner felt “extremely relieved. Hopeful for a healthy future. Excited to get her back to our family and our other pets.”

Mollie went home to recover and heal.

About 10 days after surgery, the biopsy report came back.

The pathologist did not see any evidence of cancer. No evidence of a tumor, not even a benign one. The entire mass was one big pocket of blood, called a hematoma, a completely benign condition.

So what’s the moral of the story?

Here are my thoughts, based on years of experience, and not “dogma” or “belief”:

1. To date, I have not met a single human being who has microscopic vision and can diagnose cancer by looking at a mass. If you’ve read this blog for any length of time you may remember reading a blog with a title that sounded like “When everybody is sure it’s cancer.”

www.drphilzeltzman.com/blog/when-someone-tells-you-your-pet-has-cancer

and

www.lrvss.com/when-everybody-is-convinced-its-cancer

and

www.hrvss.com/when-everybody-is-convinced-its-cancer-part-2

In these blogs, I described several patients who were supposed to have a cancerous mass, and did not, based on the biopsy report.

2. To date, I have not met a single human being who could give a cancer diagnosis based on an X-ray (bone cancer may be an exception).

Of course, we can (and should) have an impression, or a list of diagnoses, or a few thoughts, or a strong suspicion.

Saying “your dog has spleen cancer” based on an X-ray is simply not possible.

Saying “I am very concerned this is spleen cancer” is a bit more humble and scientifically accurate.

3. Even with an ultrasound, it would be difficult at best to be sure the mass was cancerous.

Now, if Molly had 1 or several masses in the spleen, and 1 or several masses in the liver, sure, it would have been much more likely to be spleen cancer that spread to the liver.

And since the most common cancer of the spleen is hemangio-sarcoma, it would have been a reasonable suspicion (still not a certainty).

4. As I implied above, the only way to know what a mass is, is to send samples to the lab. Most people however don’t like to stick needles in a spleen mass, for a few reasons:

– there is a theoretical risk of causing internal bleeding

– if it were cancer, there is a risk of spreading cancer through the belly. Cells can come out of the holes left behind, and the needle can spread cancer cells along its path. This process is called seeding.

And this is the frustrating thing about spleen masses – and others. It’s maddeningly difficult to be sure about the diagnosis without the benefit of surgery and a biopsy.

5. Frustrated by this lack of certainty, multiple vets (surgeons, internists, oncologists, etc.) have tried to find a way.

I recently heard of a test out of Purdue University (Indiana), called the t-stat test.

Some surgeons like it, some don’t. The nay-sayers believe it’s not objective enough.

6. Even yours truly tried to come up with answers. Years ago, during my surgery residency, I started a research project based on hundreds of spleen masses.

I was trying to prove that the bigger the spleen mass, the less likely it is to be cancer.

The hypothesis of the study was that a cancerous mass is more likely to cause serious health issues, and therefore the patient is less likely to live long enough for the mass to get beyond a certain size.

Logical enough, right?

In the end, we abandoned the project, after months of research, testing, and statistics.

I don’t give up easily, but we had to admit our failure.

It was simply not possible to predict the diagnosis.

Size doesn’t matter.

7. And then there is the fact that Mollie’s owners were told that removing the spleen is “dangerous” because “the tumor is highly vascularized” and “she would likely die on the table.”

Well… removing the spleen (along with a mass) is a common surgery, performed commonly by family vets, ER vets and surgeons.

– It is dangerous?

Performing surgery on a dog who is actively bleeding internally can be risky, yes, but removing the spleen is precisely the way to stop the bleeding. I would say that removing the spleen is a pretty common surgery.

– Is the tumor highly vascularized?

Sure, like many tumors. They still can be removed safely.

– “She would likely die on the table.”

Possibly.

But many others in the same situation survived the surgery.

The risk of surgery – and anesthesia – should be openly discussed between the vet and the owners, based on facts and scientific evidence.

Bottom line: with the proper guidance, and a bit of humility, Mollie could have been helped 9 months before she did.

Had she not had amazingly dedicated owners, she could have died at the ER clinic 9 months earlier.

Had she not had incredibly loving owners, who one day realized “wait a minute, it’s been 9 months, Mollie should have died of cancer, maybe this is not cancer, maybe it’s time to remove this thing from her belly”, the mass would most likely have ruptured, she would most likely have bled internally, and she quite possibly could have been euthanized – for real this time.

It would have spared them 9 months’ worth of “stress, anxiety and panic.”

Mollie is one lucky pup.

She’s lucky she had the owners she had.

They offered her a life-saving surgery.

And based on the diagnosis, there is a good chance this will not have any consequences on her lifespan.

In the end, Mollie’s owners writes: “We are very happy with our experience at LRVSS. Everyone has been helpful and pleasant. We are very grateful.”

If you would like to learn how we can help your pet with safe surgery and anesthesia, please contact us through www.LRVSS.com

Never miss a blog by subscribing here: www.LRVSS.com/blog

Phil Zeltzman, DVM, DACVS, CVJ, Fear Free Certified

Pete Baia, DVM, MS, DACVS

www.LRVSS.com